This summer, Niki and I were awarded an alumni artist residency at Columbia College Chicago. For two months, we used the gallery as our studio and then transformed it back into a gallery for the exhibition of photos, costumes, and set installation. During the residency, the Columbia exhibitions staff sat down with us to discuss the visual choices, social contexts and concerns, art historical references, and collaborative processes involved in our on-going collaboration, Muse.

Use of Metaphor

How do you address gender through the use of metaphor?

James Kinser (JK)

Visual metaphors are very potent reference tools (purse = woman, neck tie = man), and I love to play with them. They are effective tools for challenging preconceived gender associations. A lot of the costumes I make have a deep V neckline, and there’s several reasons for that. First, it reads feminine, despite the fact that if it were worn by a woman it would show a pretty hefty amount of cleavage. Second, it’s a neckline that we rarely see in men’s ready-to-wear fashion. And lastly, it’s a little bit sexy without being vulgar.

Similarly, the waist of several of the costumes for the Muse series align with the natural waist (at or slightly above the belly button) instead of the waistline where most men’s pants fit. Raising the waist tends to read more feminine since it hints at a more hourglass silhouette. Other visual metaphors, or hints of gender play as I like to call them, can be found in hemlines, sleeve lengths, and of course, the use of rhinestone/sequin embellishment.

Of all the costumes I have designed and constructed, I think the rhinestone football and football costume most overtly exemplify this mashup of gender, object, and metaphor.

First, I covered an entire football in rhinestones and then made a costume to go with it. Football became a metaphor for masculinity, aggression, what society said I should be. (I endured my fair share of harassment from that camp of athletes in high school and college). I also covered football pads and undergarments in rhinestones and fringe – materials that, to me, represented celebration and pride. Ultimately, the football costume became a visual metaphor for the reclamation of those negative experiences and ownership of them as just something that happened, without any sting. Essentially, I could find more balance within myself simply by mashing up these disparate objects/visual metaphors.

Niki Grangruth (NG)

In terms of symbolic gender, we are referencing both masculine and feminine genders within the images to create a character that falls in between the gender binaries. Moving beyond gender, biological sex also becomes an important element.

In the image Black Magic (after Magritte) James appears to be biologically female, but again this is an illusion or performance. I feel that while we tend to think of sex and gender as existing on one spectrum, it actually exists in a three dimensional form with various points of intersection. One term I particularly like is “two-spirit” which is a term used by some indigenous cultures to describe a person who possesses and expresses qualities of femininity and masculinity. Our intent is more to question the socially-constructed gender binary than to provide politically correct definitions for gender expression. Certain features reference the masculine, such as James’ beard, his body shape, and his angular jaw line. His biological sex is not hidden, but instead celebrated in combination with features that emphasize the feminine, such as the posing, costuming and props.

Objects and Gender

How as an artist do you use objects, style, or symbols as devices in your works? How do objects became stands in for genders or metaphorical genders?

NG: Both James and I use gendered materials in our own work, as well as our collaborative work. For me, this is out of an interest in the way society assigns gender qualities to inanimate objects, which can seem very absurd. From a young age, mainly due to gender-based advertising, we are taught that certain materials, objects, and colors are gender specific. Assigning gender to inanimate objects reinforces the gender binary, and in turn, gender stereotypes. I think that both James and I like to subvert gendered materials in a playful way to promote the questioning of preconceived ideas of gender.

JK: The practice of applying gender to objects fascinates me. Since we do not conjugate nouns with gender, we really do have freedom to look at objects with a subjective or individual point of view. It can be really entertaining (and enlightening) to look at everyday objects, assign them a gender quality, and then ask why it deserves that label. There are elements in clothing that I have thought of as belonging solely to women or solely to men. To my eye these associations are based on cultural influence. For example, the skirt squarely belongs to women despite on-going efforts by American clothing designers since the 1960s. The cap sleeve, most flowing or ruffled design elements, and most sparkle, rhinestones and sequins are all considered feminine. I think of men’s clothing as the female cardinal of fashion compared to the range of expression found in women’s clothing. I suspect this is all a byproduct of our patriarchal society’s historic fear of the feminine, but that’s a whole other deep conversation.

Social Messaging

In some of your own artistic statements, you use the term “social messaging.” How do you define “social messaging?”

JK: Social messaging is the same as conditioning. I use the term to describe the direct and indirect messages around us that tell us how to behave and assimilate. In our every-day lives conditioning tends to be more subconscious since we are most often very familiar with our surroundings. Today, I think conditioning comes most prevalently from the media, television, and social media. In general, I hold a pretty skeptical view of these outlets and try to be a conscious media consumer.

Having said that, I think there are some truly spectacular messages out there in the media sphere that are really making a difference. The It Gets Better project, the HRC rainbow profile picture initiative and last but not least, RuPaul! Beyond the earth-shaking 1990s “Covergirl” days and the contemporary seasons of Drag Race, RuPaul has commonly dispersed existential messages that address the relationship between drag, authenticity, and spirituality. There are two outstanding interviews with RuPaul – one at the NYC Public Library and the other with Marc Maron on his WTF podcast. Both keenly hit at this notion of drag vs. identity/ego. Both are a serious “must listen” for anyone. I don’t want to steal or butcher RuPaul’s words, but I have to underscore his notion that identity/ego hates drag. Ego likes the contained, the finite, that which can be easily defined. Drag and gender play upends those labelled buckets, spills their contents onto the floor, and says defiantly “How d’ya like me now!? I am fierce. I am glamorous. I am strong. I. Am. Love.” And this is why the social messaging that RuPaul is fostering in the world is so important. Unlike the news media or much of ego-centric social media, at the heart of RuPaul’s message is love for one’s self, love for others, and love for the collective whole of which we all compose. And as far as social messaging goes, that is something I can stand for!

Follow on Social Media

Facebook: Muse Summer Residency

Instagram:#GenderMuse2015

Twitter: @Nikigr17, @JKintheStudio, #MuseResidency

Art History and Representation

What are your thoughts on the canon of art historical works that you refer to? Do you refer to them passively, as only a sort of source material for composition, or are you engaging the contexts of their histories as well?

NG: I feel that it is important to address our appropriation of these works – they become reinterpretations rather than recreations. We critically analyze each reference piece through the veil of contemporary issues surrounding gender non-conformity. There is a power that comes from the rich history, the perfection of craft, the resolved composition and an element of the unexpected in these works. I find that the aura surrounding [these] particular works in art history very enthralling.

The works we choose to reinterpret are painted by male master painters that depict female subjects. In our images, we question this traditional relationship simply in my being a female studying a male subject and by depicting James in a more active role through the use of posing and expression – the subject becomes both artist and muse. The reference to painting in my work is a bit more complicated. I’m not necessarily interested in the fact that the reference imagery is itself a painting, but am drawn to specific elements in the original works.

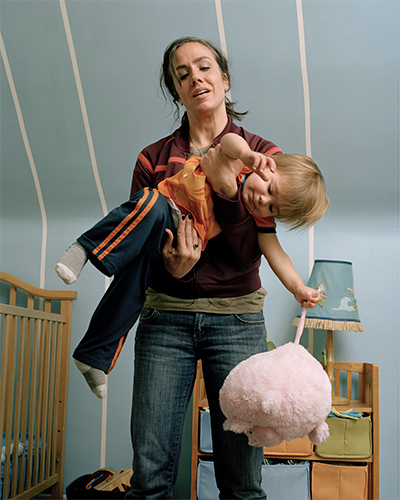

For example, my photograph Our Lady (with child and stuffed animal), 2009, from my series, New Madonnas, looks at the idealization and prevalence of maternal ideals. There are certain gestures, poses, and compositional elements in paintings of the Madonna and Child that perpetuate the ideal. In my work, I both use and subvert those elements. I am also particularly interested the idea of nachleben, a German word meaning the “after life” of a work, teaching or philosophy. We understand our present visual culture based on a history of imagery. This has been an ongoing interest in my work and research.

Collaboration

You both have been working together for eight years on the Muse project. Do you consider the works themselves to be collaboratively authored? How does that disrupt the relationship between artist/muse?

JK: Authentic collaboration comes from a truly egoless place. It is the act of opening one’s self to another, and in return, giving them the space to do the same – an artistic marriage of sorts. Niki and I have been collaborating on Muse since 2009 and from the very beginning, it started with a feeling – an inner ding on our authenticity meters. Something felt right and we have tended to that feeling since. For two highly sensitive and intuitive people, this process of following what most feels right works for us. It’s our way of working, and it may not be what collaboration looks like for others. It’s worth noting though, that even our process of collaboration challenges gender norms – something that I suspect allows for more distillation in the work. To intuit, feel and ask questions are all traditionally associated as feminine approaches. Yet, regardless of our respective sex or gender identity, it’s this feminine approach that allows our strengths to come forward in our collaborative process.

NG: We see the works as entirely collaborative. Our conceptual development, planning and execution of the images is completely collaborative. It is difficult for many people to accept that there are two authors to the pieces we create, I think that collaborative work is still something that the artworld has yet to truly embrace. Our creative partnership is guided by mutual understanding, respect and authenticity. Although we come from different artistic backgrounds and practice different media, our conceptual interests run parallel. This is not a project that we would each be able to execute without one another. This way of working creates a more dynamic relationship between the artists and the muse.

Gender in Fashion

What do you think of individuals like Roan Louch and gender in fashion?

JK: Over the last year, my Twitter feed was abuzz with posts about Andrej Pajic, an androgynous Australian model who was walking the runway in women’s fashion shows. Andrej now identifies as Andreja after sex reassignment surgery. Roan Louch, another androgynous model with long straight hair, stubble-less face and hairless body (except legs) embodies a similar hybrid of masculinity and femininity. Frankly, I don’t understand the stir the media whips up about these models. I look at them, and feel within me a matter of fact “yes” response. It makes sense that this barrier between what is masculine and what is feminine is being broken apart at this time.

I think what lies beyond this disambiguation of gender and sex is a more generous and respectfully human way of looking at one another. And I see the presence of Roan and Andreja as signs of our collective minds beginning to move more in that direction.

NG: I feel that the increasing popularity of androgynous and transgender public figures shows a positive direction for society’s acceptance, tolerance and celebration of nonconforming genders. However, I am somewhat wary that this will be seen as a trend or fad. I believe the nonconforming performance of gender is something to be celebrated, but with cases like Caitlyn Jenner and other celebrities, it is important that the public recognizes that their experience of gender nonconformity is often glamorized and is more accepted due to their celebrity status. This does not necessarily represent the experience of the nonconforming gender population.

I can only hope that we continue to move in that direction and that our celebration of the beauty of celebrity figures will happen with “common” people who don’t conform to traditional gender binaries as well.